Douglas Engelbart passed away earlier this month. For many years, Engelbart languished as one of the many forgotten heroes of the computer revolution. More recently, he has been rediscovered as the inventor of the computer mouse. But Engelbart’s idea that the computer could be a tool for “augmenting” the human intellect is too often confused with the modern notion of “user-friendliness.” In many important respects, the mouse that Engelbart invented was not the mouse that we use today. It resembles it in terms of its fundamental technological architecture, but as part of a larger socio-technical system, it is really quite different.

There has been a lot written about Engelbart in the wake of his death. The very best book on Engelbart, Thierry Bardini’s Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing (Stanford University Press, 2000) is, alas, too little read or referenced. What follows is my review of Bardini’s book, first published in the Harvard Business History Review:

Review of Thierry Bardini, Bootstrapping: Douglas Engelbart, Coevolution, and the Origins of Personal Computing (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000)

Recent years have witnessed the rediscovery of Douglas Engelbart. During the 1960s and 1970s Engelbart was a central figure in the development of several key user-interface technologies, including the electronic mouse, the windowed user-interface, and hypertext, that have since become fundamental paradigms of modern computing. In this substantial new history of Engelbart and his pioneering research on the “augmentation of human intellect,” Thierry Bardini provides a balanced and far-reaching account of Engelbart’s role in shaping the technical and social origins of the personal computer.

Douglas Engelbart’s interest in human-computer interfaces began in the early 1950s. After serving a short stint as a radar operator in the Army and working for three years as an electrical engineer at the Ames Research Laboratory, Engelbart found himself dissatisfied with his own personal and profession development. In an epiphanal moment of self-realization, he embarked on a “crusade” aimed at “maximizing how much good I could do for mankind.” He decided that the newly invented electronic computer was the ideal tool for addressing the growing “complexity/urgency ratio” of the problems facing modern technocratic society. He enrolled in a computer program at Berkeley, received his Ph.D. in 1956, and by 1959 had founded a program for the “augmentation of human intellect” at the newly-established Stanford Research Institute (SRI).

Over the course of the next several decades, Engelbart and his “crusade” played an active role in shaping the emerging science of user-interface design. Researchers at his Augmentation Research Center (ARC) pursued what Engelbart referred to as a “bootstrapping” approach to research and development. The “bootstrapping” concept borrowed heavily from the cybernetic notion of feedback: progress would be achieved by “the feeding back of positive research results to improve the means by which the researchers themselves can pursue their work.” The result would be the iterative improvement of both the user and the computer. The augmentation of human intelligence was dependent not only on the development of new technologies, but on the adaptation of humans to new modes and mechanisms of human-machine interaction. Several of the key technologies invented at ARC, including the chord keyset (an efficient five-button keyboard that could be operated one-handed) and the electronic mouse, required significant behavioral readjustments on the part of inexperienced users.

Engelbart’s emphasis on the computer as an augmentation device brought him into conflict with then-dominant perspectives on user-interface research. In 1960 the MIT psychologist J.C.R. Licklider published a highly influential paper on “Man-Computer Symbiosis” that conceived of human-computer interaction in terms of a conversation among equals. In Licklider’s model, the computer was not merely a tool to be used but a legitimate and complementary form of intelligence: users would be encouraged “to think in interaction with a computer in the same way you think with a colleague whose competence supplements your own.” As the first director of the Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) at the United States Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), Licklider actively encouraged research in artificial intelligence. Engelbart’s program, which was based on an entirely different assumption about the nature of the human-computer relationship, was thus consigned to the margins of the institutional networks that developed under the auspices of IPTO and ARPA.

In the course of their research, ARC researchers produced several important technological innovations: chord key set, the electronic mouse, and the oN-Line System (NLS) for storing, retrieving, and linking between data. Bardini describes the development of these technologies in considerable detail, but his emphasis is on a much more significant construction: the computer user. Building on recent research in the sociology of technology, Bardini argues that “Technical innovators such as Douglas Engelbart also invent the kind of people they expect to use their innovations.” In Engelbart’s case, this user was a skilled knowledge worker, typically an experienced programmer. Embedded in the bootstrapping approach was the assumption that the user already knew how to operate the technology, and could therefore focus on the adaptation of his or her own practices in an optimal feedback loop with the computer.

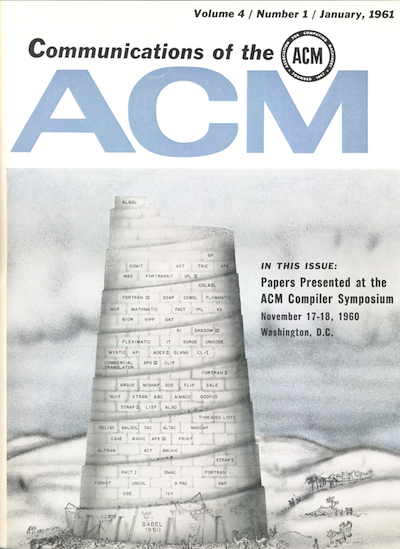

The idealized computer user invented at ARC contrasted sharply with the virtual user invented at the nearby Xerox Corporation Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). At PARC computer users were assumed to be inexperienced, non-technical, and child-like: the focus of PARC research was therefore on the development of “user-friendly” interfaces that required no significant learning or adaptation. The graphical user interface developed at PARC was based on common, real-world metaphors: using a standard keyboard, users “typed” on electronic “paper” and manipulated objects on a virtual “desktop.” The result was the WIMP (windows-icons-mouse-pointer) interface that since become conventional for most personal computer operating systems. Although PARC researchers adopted several key technologies from ARC, including the mouse and the windowed user-interface, Engelbart considered their “dumbed-down” interface to be a betrayal of the real power of the computer.

For most of his career, Engelbart and his ARC researchers were consigned to the outskirts of the computer science community, overshadowed by the more visible research programs funded by IPTO and Xerox PARC. Although many of Engelbart’s fundamental ideas and innovations the discipline have since been recognized and adopted, his larger “crusade” has largely gone unrealized. The strength of Bardini’s narrative is that it moves beyond the simplistic “misunderstood genius” genre to provide a rich account of the many social and political factors that determine how and why certain ideas and technologies get disseminated and adopted. Overall the book is accessible and compelling, and although not primarily targeted at business historians, provides valuable insights into the fundamental theories and innovations that underlie modern computing technology.

Follow

Follow