The much-hyped and controversial website Vox.com (“Its mission is simple: Explain the news”) has been taken to task for a recent article claiming that the speed of adoption of new technologies has been speeding up. They have been criticized not only for their uncritical and misleading use of data, but also the way in which they approached the process of making corrections to the original article.

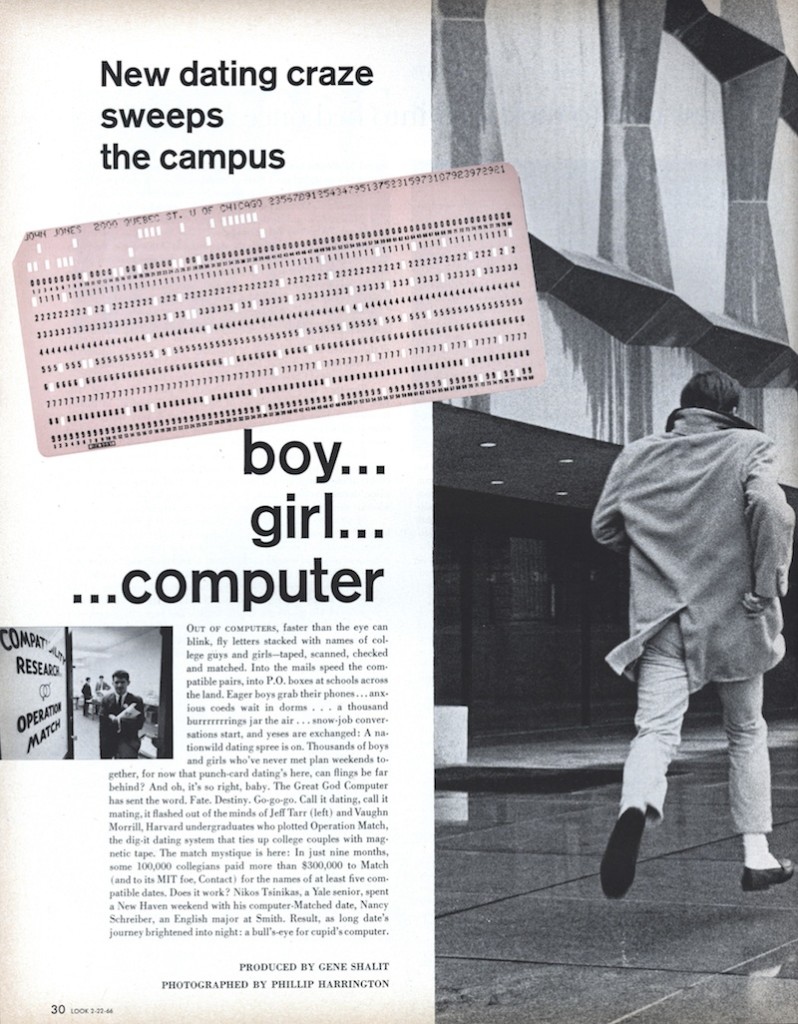

The actual claim made in the Vox.com piece about the supposed accelerating pace of technology is not at all original. In many ways, it would be hard to find a more conventional piece of “wisdom.” It is true that their reliance on Youtube videos allegedly showing how children today cannot figure out what a Sony Walkman might be for is particularly anecdotal (“kids say the darndest things!”), but if you were to ask the proverbial man or woman on the street about technology this is pretty much exactly what they would say.

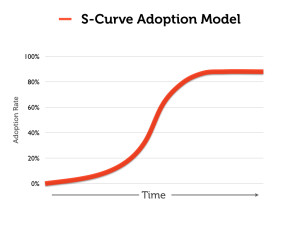

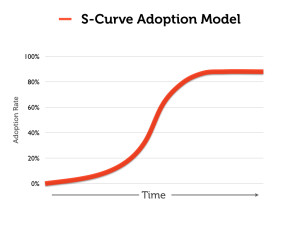

The Vox.com article is a prime example of what I teach my students about the dangers of the “s-curve.” The s-curve has become something of a cliche in pop-economics writing about the history of technology.

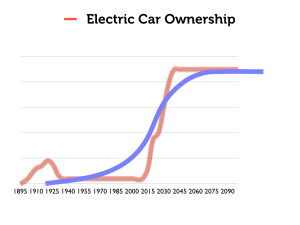

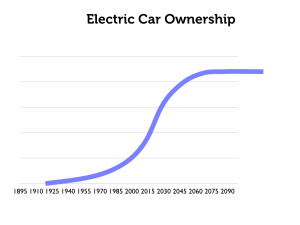

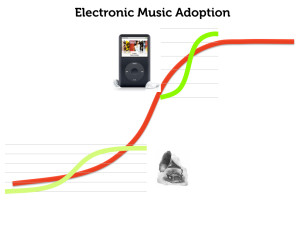

Here is the basic form (and premise) of the s-curve graph (adapted from a recent lecture in my Information Society course):

The idea is that the adoption of a novel technology often starts slowly, then accelerates rapidly as the technology gets perfected, and then tails off as the technology becomes mainstream. The “fact” that the length of these s-curves are getting increasingly shorter is the premise behind many a “technology is driving history” argument — including the recent one made by Vox.com.

The problem, of course, is that by fiddling with dates, scale, or detail, you can fit any technological phenomenon into a convenient s-curve.

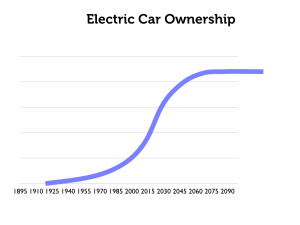

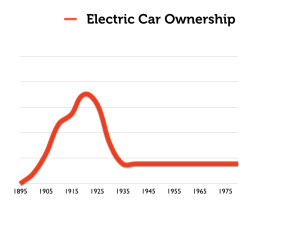

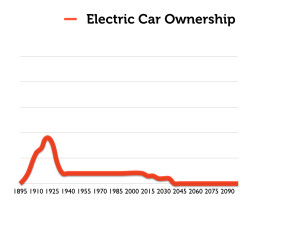

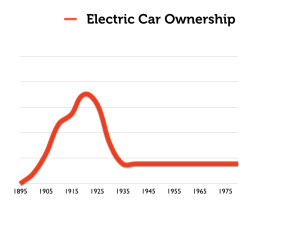

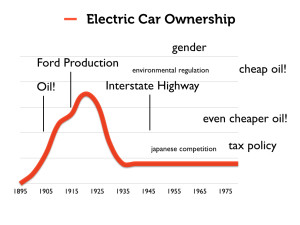

Consider for example this illustration of the adoption of electric-car technology:

In the surface, this seems to capture the s-curve phenomenon neatly.

But let us provide a more historically-accurate graph of electric-car ownership in the 20th century, which actually looks more like this:

The really interesting phenomenon here is how popular electric cars were in the early decades of the 20th century. Here is a close view of that period. Notice that ownership peaks at about 1920.

Here is a picture of an Edison manufacturer electric car from this period

and, just for fun, a picture of Colonel Sanders standing next to his electric car

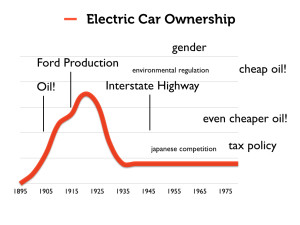

The point is that these vehicles were popular. It was only a combination of social changes (electric cars get gendered female — they become known as “chick cars,” so to speak), technological innovations, political changes (cheap oil!), etc., that gasoline powered vehicles become standard. [For more on this history, see David Kirsch’s The Electric Vehicle and the Burden of History]

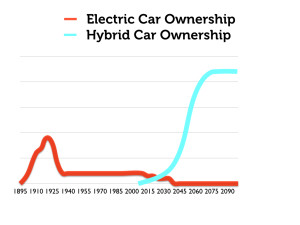

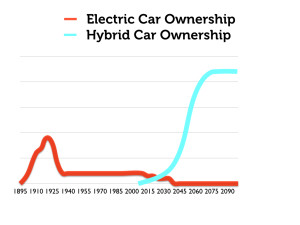

If we overlay a graph of the adoption of hybrid gas-electric vehicles onto this history, we can begin to explain the resurgence of electric vehicles in the early 21st century. (Again, the explanation is social, political, and technological).

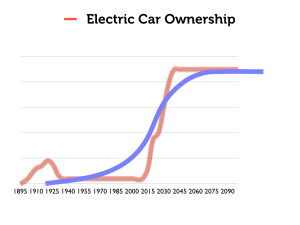

Finally, we could overlay all of this with an s-curve that seems to neatly capture the phenomenon. But this would provide an entirely false picture of the history of the electric car, and would suggest a coherence to the s-curve model of technological adoption that is entirely inconsistent with reality. The story of the electric car is not one of gradual (albeit slow) transformation from niche to mainstream technology. The s-curve does not fit.

So how does this relate the the Vox.com article?

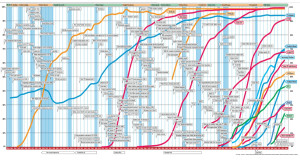

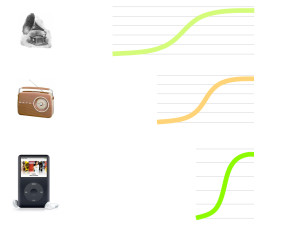

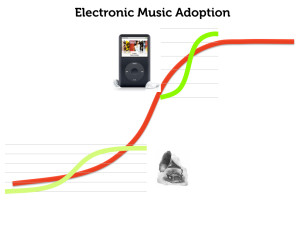

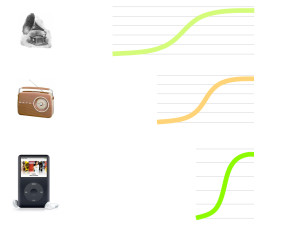

Depending on how you chose your endpoints, you can always construct a picture of accelerating adoption. Take for example the curves associated with various music reproduction technologies:

This seems to support the idea that the adoption period of the iPod was much shorter than that of the phonograph. This is probably true. But what does it tell us? If we think more broadly about the underlying phenomenon, which is music reproduction, we get a different story.

Yes, consumers took to the iPod much more quickly than the Sony Walkman. But this is because the Sony Walkman had already done all the work — social, economic, etc. — that accustomed people (and music publishers) to the idea of portable, mass-reproduced popular music. And the Sony Walkman in turn was building on decades of work — again, social, economic, and legal — that had already changed the way in which Americans consumed music. What do you think was the more revolutionary moment of technological change? When you upgraded your Walkman to an iPod? Or when your grandparents first heard recorded music on a phonograph? It seems pretty clear to me that the latter was the much more significant (and disruptive) experience.

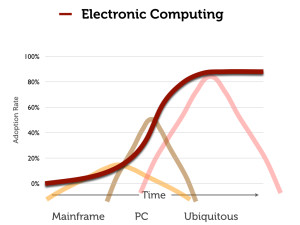

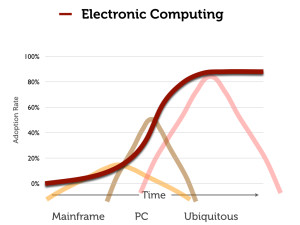

How does this relate to the history of computing? My lecture on “dangerous s-curves” was created specifically to talk about the adoption of electronic digital computing technology, and in particular the personal computer. It is easy to interpret the history of the PC as a part of a “changing pace of technology” argument — but only if you ignore the many decades of technological and social work that went into create the tools, user-base, and technologies (particularly software) that made it easy to adopt this “new” technology.

The s-curve for “computing” subsumes a number of related but quite different curves (and technologies) that cover the rise — and fall — of the main-frame and mini-computer. The PC was not just the latest in a series of developments in computing. In many ways, it came out of a very different technological trajectory.

The point is, again, that you can force this history into a s-curve that supports whatever argument you want about the course and pace of technological development. But to do so conceals much more than it reveals.

Follow

Follow