The 1960s were characterized by a perpetual “crisis” in the supply of computer programmers. The computer industry was expanding rapidly; the significance of software was becoming ever more apparent; and good programmers were hard to find. The central assumption at the time was that programming ability was an innate rather than a learned ability, something to be identified rather than instilled. Good programming was believed to be dependent on uniquely qualified individuals, and that what defined these uniquely individuals was some indescribable, impalpable quality — a “twinkle in the eye,” an “indefinable enthusiasm,” or what one interviewer described as “the programming bug that meant … we’re going to take a chance on him despite his background.”

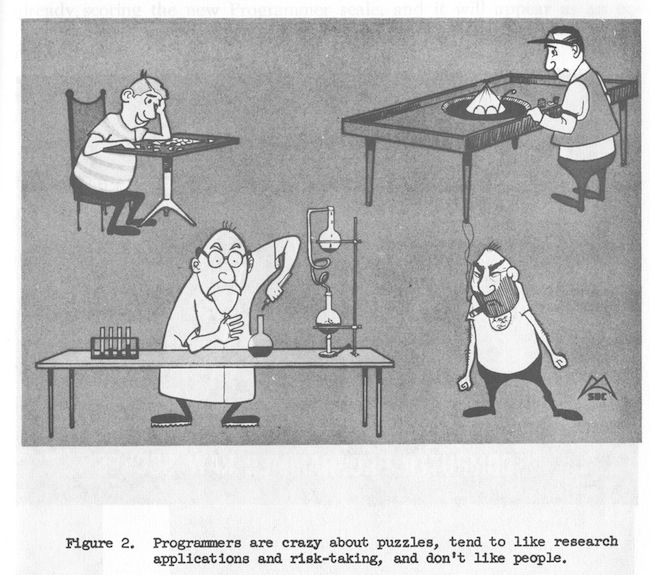

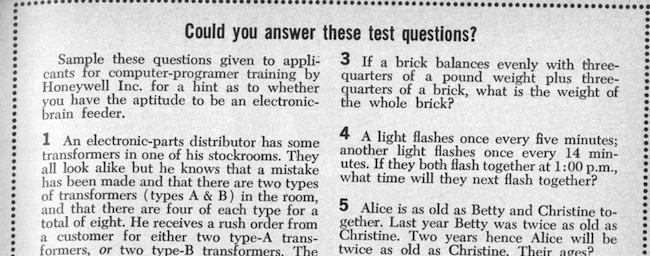

In order to identify the members of the special breed of people who might make for a good programmer, many firms turned to aptitude testing. Many of these tests emphasized logical or mathematical puzzles: “Creativity is a major attribute of technically oriented people,” suggested one advocated of such testing. “Look for those who like intellectual challenge rather than interpersonal relations or managerial decision-making. Look for the chess player, the solver of mathematical puzzles.”

The most popular of these aptitude tests was the IBM Programmer Aptitude Test (PAT). By 1962 an estimated eighty percent of all businesses used some form of aptitude test when hiring programmers, and half of these used the IBM PAT.

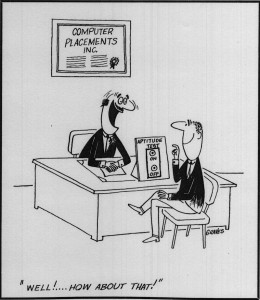

Although the use of such tests was popular (see Chapter 3, Chess-players, Music-lovers, and Mathematicians), the were also widely criticized. The focus on mathematical trivia, logic puzzles, and word games, for example, did not allow for any more nuanced or meaningful or context-specific problem solving. By the late 1960s, the widespread use of such tests had become something of a joke, as this Datamation editorial cartoon illustrates.

So why did these puzzle tests continue to be used (including to this day)? In part, despite their flaws, they were the best (only?) tool available for processing large pools of programmer candidates. In the absence of some shared understanding of what made a good programmer good, they were at least some quantifiable measure of … something.

Follow

Follow